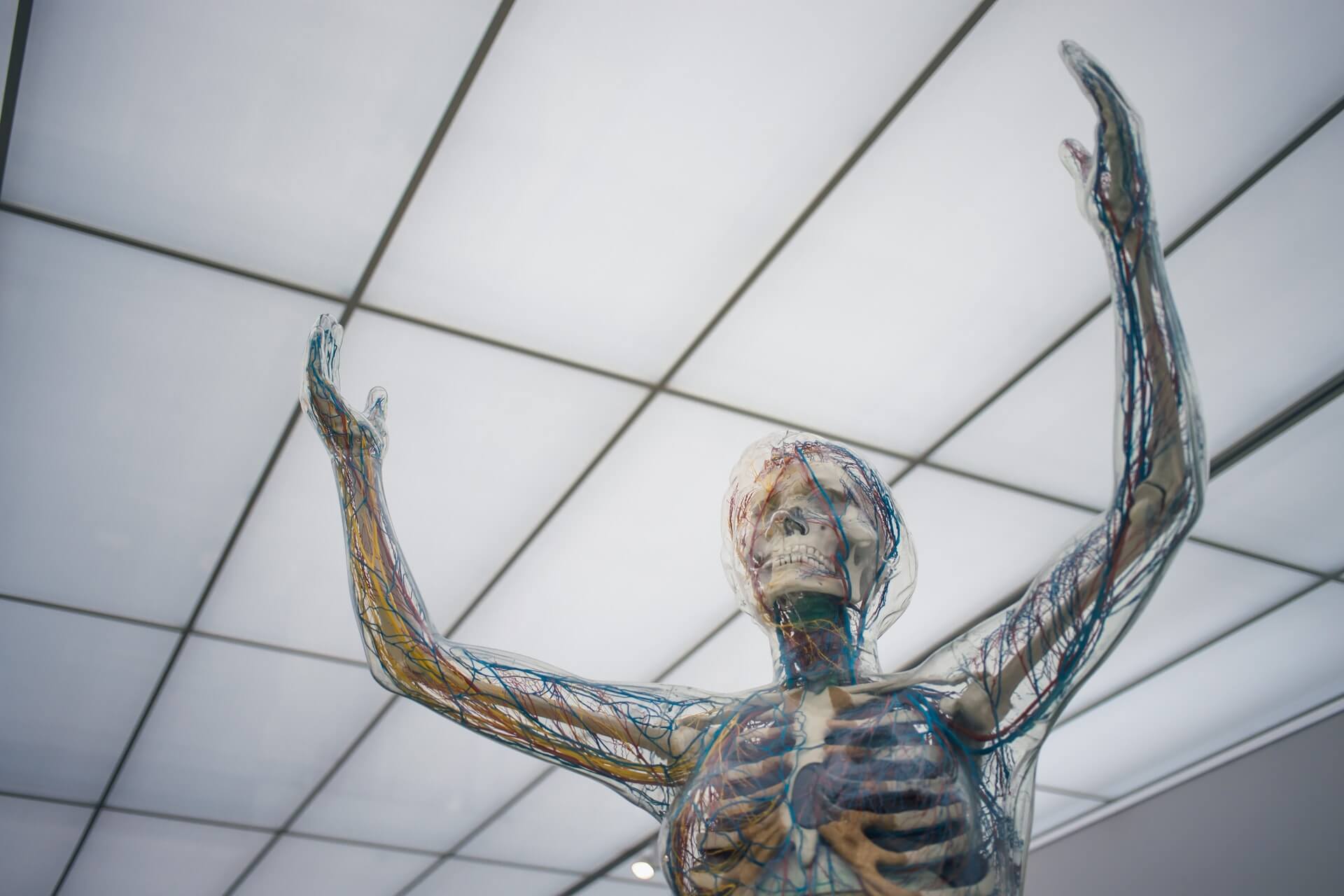

Multiple sclerosis is sometimes mistakenly called memory impairment in old age or distracted attention syndrome. In fact, this is an autoimmune disease associated neither with age nor with memory, in which our body’s immune system begins to attack its own cells, replacing normal nerve tissue with a denser one. As a result, multiple plaques or scars are formed in the brain and on the spinal cord.

Because of these lesions, many processes in the body, primarily neurological ones, are disrupted. The patient may experience muscle weakness and impaired coordination, decreased sensitivity, problems with vision and tactile sensations, pain syndromes, and so on. Often such patients (and there are over 2 million people suffering from this disease) experience problems with sleep.

Recently, however, French scientists led by Sinéad Zeidan, MD, from the neurology department of the Pitieux-Salpetriere Hospital in Paris, discovered an interesting phenomenon. As we know, fetuses and infants spend almost all of their time in the phase of REM sleep; however, with age, the amount of time we spend in this phase decreases greatly, down to about 2 hours in adults, reducing our chances of seeing lucid dreams, for instance.

Reversing REM sleep is almost like slowing down aging. Of course, it is possible to extend the REM sleep phase, but only in the context of recovery – for example, if you stop taking antidepressants or make up for a chronic lack of sleep.

The scientists, however, described a case found in a patient with advanced multiple sclerosis with an anterior pontine lesion. The pontine is the largest part of the brain stem and is a group of nerves that function as a connection between the brain and the cerebellum. Surprisingly, multiple sclerosis plaques blocked this region of the brain, apparently associated with REM sleep, due to which the patient recorded a significant increase in REM sleep – 200 minutes, or 40% of total sleep time.

Of course, this effect was discovered by chance and still requires confirmation by other experiments, but perhaps this discovery will allow scientists in the future to find a way to control REM sleep.

The article was published in February 2021 in the Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine.